“That vile thing underneath that blanket is my daughter, Anna! Oh, not the Anna you know; not that lovely girl, but a hideous parody of herself, a loathsome thing…!”

Director: John Gilling

Starring: Ray Barrett, Noel Willman, Jacqueline Pearce, Jennifer Daniel, Michael Ripper, Marne Maitland, John Laurie, David Baron, Charles Lloyd Pack

Screenplay: John Elder (Anthony Hinds) and John Gilling (uncredited)

Synopsis: Upon his return to his cottage in Cornwall, Charles Spalding (David Baron) finds a note summoning him to the nearby estate of Dr Franklyn (Noel Willman). However, when he arrives the house seems deserted. As he approaches a closed door, Franklyn suddenly cries out to him to get away—but it is too late: something darts from the shadows and bites Spalding on the neck. He staggers away and falls down the stairs, foaming at the mouth and with his contorted face dark and congested. Franklyn’s servant (Marne Maitland) hurries forward to examine the body—then looks up at the horrified Franklyn and smiles… Spalding’s sole heir is his brother, Harry (Ray Barrett), an army officer; he and his new wife, Valerie (Jennifer Daniel), travel to Clagmoor Heath to take possession of the cottage. They find the village, but when Harry enters the pub to ask directions, the locals immediately leave without answering him. Tom Bailey (Michael Ripper), the publican, is friendly, but though he gives the necessary directions he also urges Harry to sell up and get out. Things do not improve at the cottage itself: to their dismay, Harry and Valerie discover it has been ransacked—or vandalised. They refuse to be daunted, however. That night, as Valerie pumps some water, she is startled by the sudden appearance of Dr Franklyn. He tells her that he is looking for someone – his daughter, he finally adds – and, though Valerie tells him they have seen no-one, forces his way into the cottage to search it. Valerie takes the opportunity to question Franklyn about Charles’ death, which Harry has trouble believing was due to heart failure, as reported. However, Franklen explains briefly that he is not a medical doctor. Harry, meanwhile, has returned to the village to collect the luggage he and Valerie left in storage. As he crosses the moor in a cart borrowed from Bailey, the horse suddenly shies; and on the night breeze, Harry catches a strain of eerie music. He then has a strange encounter with a local character known as “Mad Peter” (John Laurie), who in the course of his disjointed mutterings insists that “they” killed Charles; he adds that “they” are responsible for the music, too. Harry takes Mad Peter back to the cottage. After supper, Peter begins to tell the others of the evil that has come to Clagmoor Heath—but breaks off when he hears the music again. He tells Harry that he heard the music on the night Charles died, then flees the cottage in terror. That night, Harry is woken by a sound outside the cottage. As he investigates, he is horrified to see Mad Peter’s blackened, distorted face pressed against a window. Peter dies speaking incoherently of Dr Franklyn…

Comments: The year 1966 was an intriguing one in the history of Hammer, a time when interesting (if not always entirely successful) one-off projects were allowed to dominate their series. Probably the two standout productions of the year were Rasputin The Mad Monk, with Christopher Lee given his meatiest Hammer role as the infamous Grigori; and John Gilling’s bleak, atmospheric Plague Of The Zombies, which in addition to its inherent strengths we now know has the distinction of being the final film to feature “traditional” zombies before George Romero came along and changed everything.

Had things been done differently, we might have been able to turn that duo into a trio with the addition of The Reptile. Unfortunately, however, in that film’s case some delicious possibilities ended up being sacrificed on the pyre of profit.

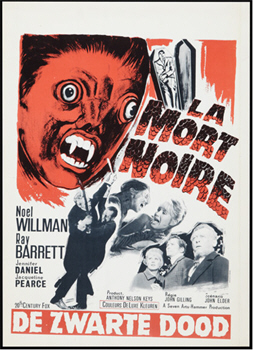

By this time Hammer was making a practice of producing pre-packaged double-bills, chiefly for their American market but also to play at home, selling two films together in a single deal; rather as AIP had done a decade earlier. In this case, confident of the drawing power of Rasputin, the studio decided to cut costs with respect to the supporting feature. Consequently, The Reptile was a hurried production with a short shooting-schedule, which made use of the still-standing sets for Plague Of The Zombies. (The studio’s attitude to The Reptile is reflected in the fact that it is much easier to find advertising art for the eventual double-bill than for the standalone film.)

The film might have survived this, but when Anthony Hinds turned in his screenplay (which he penned under his usual pseudonym, “John Elder”), the always irascible John Gilling took a dislike to it and decided to do a hasty re-write—effectively turning The Reptile into an unacknowledged remake of The Gorgon, for which he had written the screenplay two years earlier. This was a disastrous choice: The Gorgon is not, to put it mildly, one of Hammer’s stronger films, the presence of Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee and Barbara Shelley, and the direction of Terence Fisher, notwithstanding; and most of its faults can be traced to its script.

Not surprisingly, The Reptile ultimately fails at the same level—wasting its potential by putting its emphasis in the wrong place. The critical misstep was the decision to structure the film as a mystery—even though the advertising art makes what sort of story it is blatantly clear, and though the viewer is shown what is going on within the first few minutes. This in turn leads to seemingly endless scenes of people wandering about on the moors, or – invited to do so or otherwise – through the Franklyns’ cavernous house, as they “investigate” what the viewer already knows full well.

The end result is a frustrating film that, after twiddling its thumbs for far too long, ends up rushing where it should have lingered, and which never gives the audience enough of what it wants.

All that said, The Reptile is certainly not a film without virtues—with some of them found within the cast, and some in its concept. The latter is perhaps its most significant aspect: though it never makes enough of this point, this is a film that sits comfortably within that subset of historical Hammer films, horror and otherwise, that take a revisionist look at “the Empire” and British interference in many corners of the globe; yet another tale of colonial chickens coming home to roost.

The Reptile opens with one of its lengthy wandering scenes, as a man to whom we will not be introduced until after he is dead walking across the moor to his cottage, finding a note and, in response to it, setting out for the biggest house in the isolated neighbourhood. The lights are on but – as they say – it seems as if no-one is home. The man nevertheless not only enters, but begins searching for the writer of the note—finally walking upstairs towards a closed door.

As the man reaches out for it, a second man – older, distinguished-looking, and using a walking-stick – cries out to him to get away from there. The man looks around, confused though not perturbed—until something that was lurking in an alcove seizes him and bites him savagely on the neck.

The injured man reels away, clutching at his throat, staggering towards his companion—who does no more than direct him towards the staircase. The visitor falls, landing dead at the bottom of the stairs with froth around his mouth and his face discoloured.

The noise brings running a foreign servant who inspects the body—and smiles up at the house’s owner, who backs away in horror. On the landing where the attack occurred, he discovers the note dropped by the dead man, which brought him to the house…

The servant, meanwhile, is busy disposing of the body—helpfully leaving it in the local cemetery, before disappearing into the night…

(Never named in-film, and referred to only as “the Malay” in the credits, the servant is played by the Indian-born actor, Marne Maitland. For much of the film his character’s designation is the only hint offered as to where this story’s events were set in motion.)

We now learn that the dead man was a certain Charles Spalding—whose cause of death, mind you, is ruled “heart failure” by the less than competent local coroner. We then get one of The Reptile’s intentionally funny moments, as well as being clued in on exactly how bad things are getting in the village of Clagmoor Heath, with the vicar carrying out an hilariously perfunctory funeral service, his bored demeanour suggesting he’s done little else lately but perform such ceremonies.

Charles’ property is bequeathed to his brother, Harry, a Guardsman currently on leave—presumably in order to get married, as he brings a new wife, Valerie, with him to the solicitor’s office. The solicitor warns them that Charles has left very little in terms of money, and tries to discourage them from making their home at the cottage—as, indeed, does everyone that the newlyweds subsequently meet.

In fact, this is one of The Reptile’s numerous dangling plot-threads. It produces the traditional, “We don’t like strangers in these parts” attitude, with the locals stalking silently from the pub when Harry Spalding walks in—but why, when they must know very well that the danger lies elsewhere? And if, conversely, they are trying to warn the Spaldings off, why not be explicit about their situation, or at least more so? In fact, it would have been more appropriate if the Spaldings had been greeted with the “Borgo Pass Response”, that is, a refusal on the part of the locals to go (perhaps in transporting the luggage) anywhere near the Franklyns’ house.

It makes no sense—unless Charles Spalding did something to render himself obnoxious in the village; but if that was the case, the film never deigns to share. (At one point we do hear Spalding referred to as “obstinate”, but typically for this film, it leads to nothing.) Nor does there seem any purpose in the wrecking of the cottage. An offended villager insists that none of them were responsible for that—meaning that Franklyn or his servant were; but again, why? Were they looking for something, and if so, what? No-one knew that Harry and Valerie were coming, so it can’t have been to dissuade them from staying.

And this is exactly what I mean about The Reptile being a frustrating film: you end up fretting over these side issues, which really don’t have much to do with the main action, yet keep getting in the way of it.

So one way and another, Clagmoor Heath is less than welcoming to the newlyweds—but they dig in their heels and set about tidying up their new home. When they earlier arrived at the local train station, they found it deserted (of course) and were forced to leave their luggage and walk; with Valerie taking only her black kitten in a small carrier. The luggage finds its way to the pub, and so does Harry—in the first place to confront the villagers over the state of the cottage.

When he has succeeded in clearing the pub for a second time running, an apologetic Harry invites Tom Bailey to take a drink with him…

One of The Reptile’s main strengths comes in a very unexpected form: namely, the performance of Michael Ripper as Bailey. By saying “unexpected” I do not mean to imply that Ripper was not a good actor, but rather that he rarely got a part this big, or this important—in fact, you could reasonably argue that Bailey is as much this film’s hero as Harry Spalding (though “heroes”, in the usual sense, are thin on the ground).

Though he was always effective in the innumerable supporting roles and bit parts that made up most of his career – certainly his Hammer career – Ripper here shows what he could do if given then chance, and makes us regret he wasn’t given one more often. Both amusingly and delightfully, Ripper is effectively this film’s Van Helsing, finally taking the lead in the investigation of the true cause of the outbreak of strange deaths; even though, for plot purposes, it is Harry who is prominent during the film’s climax.

Another amusing touch in the pub scene is the character of “Old Garnsey”—a role experience would have prepared us to expect to find occupied by Michael Ripper! Instead it is George Woodbridge who takes umbrage at Harry Spalding’s accusations about the cottage, and refuses to drink with him.

Meanwhile, Valerie is having a strange encounter of her own, when Dr Franklyn forces his way into the cottage, searching for his daughter. Valerie is offended by his attitude, but he takes no notice. As he turns to leave, Valerie promises to tell Anna, if she should see her, that her father is looking for her. Franklyn replies frostily that she will already know…

While Harry is bringing home the luggage in a cart borrowed from Bailey, he hears music drifting over the moor. He is then attacked by someone who turns out to be Peter Crawford – “Mad Peter”, as the villagers not inaccurately have it. Harry is unhurt, and his exasperation turns to eagerness when Peter’s mutterings suggest he may know something about Charles’ death. He therefore carries him to the cottage, promising supper in exchange for information.

Long-time character actor John Laurie has perhaps a bit too much fun as Peter, but he manages to keep the ‘Odious’ out of the ‘Comic Relief’; and besides…he’s not around for long…

Later, when the Spaldings have forced Peter to stop eating and start talking, they have hopes of learning something concrete about Charles’ death, but they get no more than that, “They were responsible”…as they were responsible for bringing evil and corruption to the village. Even as Harry presses for more, Peter leaps to his feet at the sound of the strange music. He tells Harry he heard that music on the night Charles died, before rushing out into the night…

…only to return some hours later, frothing at the mouth and with his face dark and distorted.

Harry goes running off to get Franklyn—only to learn to his dismay that he is a Doctor of Theology, not a medical doctor. Franklyn, very grudgingly, agrees to see Peter—but he has died before the men arrive. Unmoved, Franklyn observes that Peter was a known epileptic and no doubt died of a fit; he promises to make the arrangements for burial, before curtly taking his leave.

Franklyn’s coldness here highlights another of the film’s loose ends: twice when he thinks he’s alone (the second time he isn’t), Franklyn visits Charles Spalding’s grave, placing a wreath upon it and removing his hat as a sign of respect. We’re given no hint of any friendship or indeed any relationship at all between Franklyn and Charles, and can only conclude that the former’s overt remorse in this particular case is because Charles was a gentleman.

After Franklyn has gone, Harry carries Peter’s body to a storage room…where the Malay finds and inspects it…

Only Tom Bailey and the Spaldings attend Peter’s funeral; Bailey comments that he had friends, but they are, “Afraid of what he died of” – the “Black Death”, as it has become known. When Valerie presses, Bailey comments that the village has no doctor (which is ridiculous: a better answer would have been that the doctor was one of the victims; who else so likely to ask awkward questions and recognise wounds, after all?). We also learn that the once-a-month coroner apparently calls everything “heart failure”, which reawakens all Harry’s suspicions about Charles’ death.

Valerie packs Harry off to the pub for a drink and walks home by herself. As it turns out, the pub is closed, and the men end up having a brandy in Bailey’s parlour, where he at last says a few of the things that are on his mind. It turns out that even as Harry is a soldier, Bailey used to be a sailor; both of them have knocked around the world and seen many strange things; but while Harry is still certain there must be a “logical explanation” for all the deaths, Bailey isn’t so sure…

In fact, Bailey is thoroughly frightened, and he makes it clear that if Harry wants to investigate, he’ll be on his own.

At the cottage, Valerie has a visitor: it is Anna Franklyn, who is arranging numerous vases of flowers as a welcoming gift—and also to soften the memory of Peter’s ugly death. Anna presses an invitation to dinner that night upon Valerie, and she accepts. The two look like making friends until, when Anna goes to fetch water, she finds the Malay lurking in the bushes. His intense gaze is distressing to her: it seems almost to force her back into the cottage.

Inside, Anna confuses Valerie by insisting in a panicked manner that she has to go. However, by the time she reaches the door again, Dr Franklyn is standing there. He berates Anna for paying the call without his permission, snarling at Valerie, too, when she reacts to what strikes her as his absurdly disproportionate anger. Both then apologise—Franklyn for his manner, and Valerie for butting in. When Valerie mentions the dinner invitation, Franklyn is taken aback but finally seconds it.

As Franklyn and the Spaldings chat over a pre-dinner drink, however, Anna doesn’t join them: Franklyn explains that she is being “punished”.

It is hard to know whether, like Valerie, we are intended to find Franklyn’s control of his daughter unreasonable, or see this as just a stern Victorian father in action; young women of the time were, after all, often treated like children rather than adults, whatever their age.

But the truly curious thing is the way that Franklyn’s attitude towards his daughter swings from cold condemnation to a warm and obvious love. To the Spaldings he speaks of her with affection, and with gratitude, too, for her uncomplaining companionship as he travelled in distant lands for his work—his research into Eastern religions…

After dinner, a sari-clad Anna is permitted to join the rest. The party immediately separates, with Franklyn sending the women away on the pretext of Anna showing Valerie her many pets—although given the lines of stacked cages, they don’t really look like pets…

This is yet another of the film’s loose ends. The inference is clear enough: were-Anna bites humans to kill, but she feeds upon small animals. However, as far as we know Anna never transforms, or is transformed, except when a victim has been prepared for her; consequently, we never see her that way except during the film’s closing sequence, which requires her to be incapacitated. So does she really feed on her “pets”, or was this touch merely meant as a disturbing detail? Conversely, is this the real reason Anna didn’t join her guests for dinner?

Having gotten Harry alone, Franklyn joins the chorus and tries to persuade him to leave the cottage—as Anna correctly predicted to Valerie that he would; taking the opposite stance from her father and begging Valerie to stay…

Downstairs, Franklyn demands that Anna play for them, despite her evident reluctance. Her choice of instrument is the sitar, with which she displays great skill. But then something changes: as the music that Anna is playing shifts to become that of the moors, suddenly it seems to be she who is dominating Franklyn, holding him with a challenging, defiant gaze. The effect upon Franklyn is dramatic: he leaps to his feet, snatches the sitar from his daughter’s hands, and smashes it. He then orders Anna out of his sight, as the Spaldings beat a hasty retreat.

As Anna weeps in her room, pressing her fingers to her temples, the Malay enters—offering her Valerie’s kitten; though he makes her plead for it. She is caressing the little animal when her father bursts in, telling her that they are leaving—only to be coolly contradicted by the Malay. Franklyn threatens him furiously, but receives only a smile: he could kill him, agrees the Malay, but that would not free him; and what would happen to Anna?

“You will be punished to the end of your miserable days,” he croons.

The following morning, Bailey shows up at the cottage with some supplies—but also to tell Harry that he has changed his mind about investigating the mysterious deaths; really changed it, so much so that when Harry calls upon him late that night, he is horrified to discover that Bailey has dug up Peter’s body, so that they can examine it properly. What they find is a bite-mark on the back of his neck; or, more correctly, fang-marks. Harry is still absorbing this when Bailey makes his next suggestion: that they should dig up Charles, too…

And they do. It’s a much more disturbing job for several reasons, not least because Charles has been dead much longer; but they find what they’re looking for. Now they voice the idea that has occurred to each of them: they’ve both been to India, and they know what the bite of a king cobra looks like. Rationalist Harry continues to resist the implication, but Bailey accepts what he knows must be true.

Harry is withdrawn and silent upon his return to the cottage, but his thoughts are diverted by a note addressed to him from Anna, who declares herself in danger and begs for his help. After witnessing Franklyn’s violent outburst, the Spaldings have no difficulty believing this, and Harry sets off without hesitation. Some of us, however, recall the note that led Charles to his doom…

Harry finds an open door, which leads into the room in which Anna’s “pets” are kept—including Valerie’s kitten, a stout padlock on its cage. Time presses, however, and after an encounter with a statue of a cobra, Harry continues to move quietly through the house. He does not notice that the Malay is watching; though we notice he is not interfering. As happened with respect to Charles, Franklyn suddenly appears, urging Harry to get away; and as also happened with respect to Charles, he’s too late…

This is our first proper look at Anna in were-cobra mode, and it’s a mixture of the brilliant and the distinctly unsatisfactory. The brilliance lies in the fact that Roy Ashton went all out on his prosthetic, designing something which entirely encased Jacqueline Pearce’s head (Pearce, who was claustrophobic, was is misery while wearing it); and if it doesn’t look particularly cobra-like, it is still a disturbing creation, shocking on its first appearance. Ashton also moulded real snakeskin to get the right texture. However, the effect is spoiled by the uneven setting of the eyes, which was done deliberately to help Pearce see while wearing the device, but gives the prosthetic an unbalanced, googly-eyed appearance. It isn’t obvious, but once you’ve seen it, you can’t un-see it, and it deflates some of the were-cobra’s menace. We might also be inclined to note that were-Anna’s fangs seem too widely spaced to have inflicted the bite-marks we have been shown.

The other problem is the eternal one of were– films: the rest of Anna is clad in some tight, slinky gown that may have been meant to look like snakeskin, but instead undermines the overall effect. She needed to be either entirely snaky – and they at least could have put her in a body-suit rather than a dress – or (more practically) to only transform above the shoulders, and to be wearing whatever clothes she had on at the time.

The other disappointment is that this, the first time we see all of were-Anna, is also the first time that she fails. Harry Spalding is gifted with an outrageous Hero’s Death Battle Exemption© here, and somehow recovers from Anna’s bite—which has killed everyone else in minutes.

I think we’re supposed to conclude that his stiff Victorian collar took most of the impact, and that Harry therefore received only a reduced dose of venom; but it’s a pretty lame excuse. A better idea would have been to have Franklyn’s warning giving almost in time and, perhaps, Harry scratched on the hand instead of being bitten. Be that as it may, Harry manages to stagger all the way home and—oh, good grief: as in Cult Of The Cobra, what we have here is someone who thinks cutting a cobra-bite on the neck is a good idea.

Sigh.

(Of course it’s not a good idea anywhere…)

However, in this universe the cutting mitigates the worst of the venom—and with a minimum of bleeding. She then rushes off to get help—to the pub, of course.

Meanwhile, the Malay – who has already slapped Franklyn around – is berating him for intervening, so that Harry may survive. Franklyn tries to say that he doesn’t care any more, but the Malay overrides him, insisting that he does – he must – for Anna if not himself. He orders Franklyn to find out whether Harry is alive or dead, waving aside his plea to be left alone:

The Malay: “You should have thought of that before you started meddling in things that do not concern you!”

Woken by Valerie, Tom Bailey accompanies her back to the cottage. Having examined the bite-mark, he speaks reassuringly to Valerie, before heading downstairs to confront Dr Franklyn who has turned up as per orders. Instinct makes Bailey tell Franklyn that Harry is dead; he adds that, since he died of the Black Death, he, Franklyn, had better not come in. “I’ll give your message to Mrs Spalding,” he concludes coolly.

By the time Bailey leaves Harry has more or less recovered, though he has no coherent memory of what happened to him.

Meanwhile, we have seen the Malay crooning over were-Anna as she writhes on her bed; and when Franklyn subsequently enters her room, it is to discover her shed skin.

(Which is clad in a nightgown. Consistency, people, please!)

Horrified, Franklyn strikes out at the skin with his walking stick, again and again and again…

Anna herself is where Franklyn knows he will find her when he goes looking: in the cavern beneath the house, lying under a blanket next to a hot sulphur spring—which, we learn later, was one of the reasons Franklyn chose this house in the first place. Franklyn pulls back the corner of the blanket with his walking-stick to reveal were-Anna’s face…and that, sigh, her eyes are closed.

Now— I must say that Valerie is a surprisingly and very pleasingly intrepid heroine, hardly batting an eyelid from the wrecking of the cottage through her lonely vigil with the dying Mad Peter to her cutting of her husband’s snake-bite; but for her to set off to see Anna at this point is just plain stupid. Okay, she doesn’t know that Anna herself is the danger; but she does know that Harry was at the Franklyns’ house when he got bitten. I think you could reasonably say that she’s asking for it…

The more I think about The Reptile, the more disappointed in it I am—because what I end up thinking about is not the film I am watching, but the one I should have been watching, had a bit more thought and care been put into it.

The unbalanced nature of the film’s scenario, with more time spent with the Spaldings than the Franklyns, becomes increasingly frustrating, something not even the presence of Tom Bailey in that section of the film can compensate for. Every time the film builds a proper tension, it dissipates it again with one of its tedious wandering-around scenes. In fact, the pacing is an issue from start to finish, and most particularly during the final fifteen minutes when, instead of building to an exciting climax, the film offers still more scenes featuring people creeping around in the dark…before serving up yet another conflagration ending, which by 1966 was beyond predictable.

However, the cast is generally effective—and though consisting of lower-tier actors, probably do the film more service than a star-heavy ensemble could have, giving a strong sense of ordinary people going through an extraordinary experience. That said, Ray Barrett and Jennifer Daniel do struggle to make an impact as the Spaldings—although a measure of that is certainly due to their having to share their screentime with Michael Ripper, who proceeds to steal every scene he shares with one or both of them. Marne Maitland has little to do but lurk around looking ominous, at least until the confrontation scene. Noel Willman does better as Franklin, although the screenplay leaves the viewer to put most of the pieces of his character together after the event.

And here we get to the root of The Reptile‘s issues. In a film so burdened with what amounts to padding, it is exasperating that we are left with so many more questions than answers about the Franklyn ménage and their mutual back-story; far more than can be excused by a plea of “ambiguity”.

It is not surprising that those moments that do reveal something of the relationship between Franklyn, Anna and the Malay are among the strongest in the film. This includes, most obviously, the confrontation between Franklyn and the Malay after the attack on Harry, in which the true nature of the power-balance within the household is revealed; but we should also note the more subtle shifting of Franklyn’s attitude towards Anna, wherein he seems to be reacting to two different people—as, of course, he is.

There is finally a revelation scene, in which Franklyn pours out the terrible truth to Valerie Spalding. Specific details come to light at this point, yes, including that it was a secret society in Borneo, that of the “Oulang Sancto”, the Snake People, whose closely guarded secret Franklyn finally discovered—and meant to publish to the world. We learn, too, that after the Franklyns fled to Singapore, Anna disappeared—and that when she came back, she was “one of them”.

But even this is not well-handled; it certainly tells us nothing that we haven’t figured out for ourselves. (And that, come to think of it, is The Reptile‘s failure in a nutshell: it keeps telling us things we already know, and not telling us what we don’t know.) What is lacking here is depth. For instance—the screenplay makes nothing of Franklyn being a Doctor of Theology, a situation which should have been rich in ironic possibilities. As it is, we don’t even know if Franklyn was led to his studies by religious faith or intellectual curiosity. We are also unsure about the extent of his guilt. Did he know what his meddling might bring about, and yet persist anyway?

And what about the cult itself? Do its members have the ability to transform, or is this for them, as it is with Anna, a form of punishment?

But it with respect to Anna that we are left with the most unanswered questions. In what sense is she “one of them”? How is her transformation triggered? How much agency does she have, and to what extent is she controlled by the Malay? Were her overtures of friendship towards Valerie genuine, a human impulse, or the setting of a trap? Does she exclaim in delight when the Malay gives her Valerie’s kitten because it’s a kitten—or because it’s a tasty snack?

While all of these points necessarily intrude themselves, it is finally upon the emotional level that we are most left in the dark. We know that Franklyn is simultaneously protective of and repulsed by his daughter, but what is Anna’s attitude towards him, as she bears the brunt of his misconduct? The sitar-scene is suggestive, but no more than that. To my mind these questions have a peculiar urgency about them, in light of the fact that, whether she has any control or not, Anna clearly knows what she is, and what she does. Presumably that is part of the curse—and a viciously cruel part.

In fact—I have rarely across a film so desperately in need of a flashback—either in the form of a prologue, or as such, here, while Franklyn is talking to Valerie. I don’t say this because I need things spelled out for me, or because I can’t appreciate subtlety or ambiguity—but because having a character say, “They transformed my daughter into a were-cobra” and leaving it at that is just not bloody good enough.

So I can’t help but envisage a version of The Reptile in which these issues were addressed—so much more snake-cult, so much less wandering around in the dark. But above all else—such a film would necessarily have given us much more Jacqueline Pearce.

It’s extraordinary to me, and depressing, that the film-makers could have had such an asset on their hands and done so little with it. With her huge eyes and striking features, Pearce was excellently cast, and she gives us enough in the sitar-scene with her eye-acting alone to suggest what she might have done with a more significant, a more central role.

I can’t help comparing The Reptile unfavourably with Cult Of The Cobra in which, for all its focus upon the human characters being hunted down, the position of its rather sympathetic “monster” is also given due weight. That film is also fully aware of what its leading lady brings to the production.

And this, finally, is why I can’t take this film to my heart as I would wish: it simply isn’t about Anna in the way that it should be; in fact, it all but pushes her aside, while it focuses upon her father’s mental and emotional state—as if that were somehow more important than the situation of a young woman forced, against her will and through no fault of her own, to be a killer. Anna’s story ought to be a tragedy; instead it’s just a monster movie.

Footnote: How much would you like to bet that this film would have been called “The Snake Woman” if another British company hadn’t nicked in first?

Want a second opinion of The Reptile? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review is part of the B-Masters’ examination of a menagerie of human transformations.

I just wanted to remind you of something. I see that this is a menagerie of human transformations, so although snake heavy now you may change course to other critters very soon. Your Terror in the Sky write up suggests you “need to get around to” Sssssss, and if this isn’t part of your were-snake plans in the near future I will have to write it up myself. And we all don’t want that.

I have seen The Reptile once so long ago that it’s a very fuzzy memory. My best memory is this magazine, just like my comic book collection not wrapped up in plastic and saved in near mint condition, but read over and over and destroyed by wear and tear. https://picclick.co.uk/Monster-World-10-1966-Warren-like-Famous-Monsters-223216887949.html

LikeLike

I’ve been “about” to do this one so long I’ve lost track of what’s next up in snake films (straight or transformative). As I said to the Rev elsewhere, there are a bunch of Asian films I probably won’t get to because of scarcity and/or animal violence.

I do love Ssssss…, though!

LikeLike

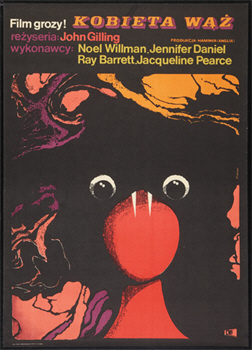

You’ve got to love those Polish posters. Clearly, the Communist government was willing to permit some artistic exploration.

LikeLike

I wonder whether the Polish poster reflects a country with plenty of artists, but not much in the way of photo manipulation skills or equipment.

To a British SF fan of a certain age, Jacqueline Pearce is a name that one immediately recognises. Not that this role has much in common with Supreme Commander Servalan.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, yes. Preaching to the converted. 🙂

LikeLike

At least a curse makes more sense than injecting venom into a pregnant woman. Even if we don’t find out much about the curse.

How did the Malay get the kitten? Didn’t Valerie ever notice it was missing?

Yes, they could have spent a few sentences connecting the “Doctor of Theology” to the cult. Was he interested in comparative religions, and studying the cult for documentation? Was he trying to make them see the error of their ways, and convert them to the True Path?

LikeLike

All three of your points/questions are exactly what I was thinking. When I read the Snake Woman review, I kept thinking that this was a case where throwing in something explicitly supernatural would have actually made the plot more believable- realtively speaking, of course.

LikeLike

and this is the place where curses are more believable than scientific experimentation – unless the experiments are well documented and explained.

LikeLike

The kitten subplot is so futile I didn’t bother getting into it much but (i) he’s constantly wandering into the Spaldings’ cottage, (ii) yes, and (iii) it gets out alive (as per final screenshot).

Yes, exactly: we never know what kind of intrusion / hubris he is being punished for.

LikeLike

Yet again, No Captions, huh? Oh well.

“it is to discover her shed skin….(Which is clad in a nightgown. Consistency, people, please”

Well, in films of that era, you can’t expect to see much bare skin…

😉

LikeLike

I’d like to see her snakeskin encased in what she wears while she has snakeskin, that’s all!

LikeLike

I saw this in high school, and really only remember Jacqueline and the make-up. Sounds like it’d be much the same if I were to rewatch it!

LikeLike

‘Fraid so. It’s one of those films you remember as being better than it is, because you only remember The Good Bits.

LikeLike

I believe Jacqueline Pearce passed away only a few months ago. The only thing I’ve seen her in was the Doctor Who story “The Two Doctors” but she was quite good in that. (She also joined the cast for the DVD commentary.)

LikeLike

OT; hey Lyz I thought you might enjoy this article on Frankenstein at 200. Too bad this exhibit is on the other side of the world from Australia as it seems right up your alley!

https://www.weeklystandard.com/paul-a-cantor/frankenstein-at-200-morgan-library-exhibition-review

LikeLike

Oops, sorry, this should have gone to General Chatter

LikeLike

Thanks to TCM, I watched this again yesterday. As you say, it could have been a good (maybe never great) movie, with just a few more lines of explanation.

For instance, the cottage being vandalized could have been because The Malay was looking for the note, and got into a fury by not finding it. On a related note, they sure cleaned that mess up fast.

What was with the animals? Lots and lots of animals? What was the scene with Valerie finding the trap for, with The Malay looking on?

Why didn’t Valerie break the window, when she was locked in the room of a burning house?

The cold sure affected the snake fast.

Lots of more horror movies in the next 2 weeks to enjoy (even if I’m making fun of most of them along the way)

LikeLike