“Your department is trying to solve two murders. There will be other murders, tonight and tomorrow night – and also next month, when the moon is full again – unless you realise, sir, there is a werewolf abroad in London.”

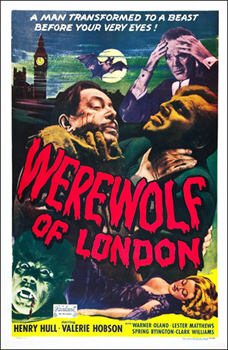

Director: Stuart Walker

Starring: Henry Hull, Warner Oland, Valerie Hobson, Lester Matthews, Spring Byington, Lawrence Grant, J. M. Kerrigan, Clark Williams, Egon Brecher, Charlotte Granville

Screenplay: John Colton, Harvey Gates (uncredited), Robert Harris (uncredited) and Edmund Pearson (uncredited), from a story by Robert Harris

Synopsis: Dr Wilfred Glendon (Henry Hull), a botanist, mounts an expedition to Tibet to search for one of the world’s rarest plants, Mariphasa lupina lumina – the phosphorescent wolf-flower, which according to legend blooms by the light of the moon, not the sun. Intending to press on into a remote valley, Glendon faces rebellion from his native crew, who believe the region to be frequented by demons. At this moment, an odd figure appears: a priest (Egon Brecher), a white man, riding a belled camel led by a local man, who the natives take for one of the demons in question; they run away in a panic. Hearing of the expedition’s purpose, the priest grows grave; he tells Glendon that he knows of no-one who ever returned from the valley. Glendon and his assistant, Hugh Renwick (Clark Williams), disregard the warning and press on alone. As they pass through a cave at the edge of the valley, Renwick experiences a strange sensation: for some moments, he is unable to move his legs. When he manages to stagger onwards, the howling of a wolf echoes across the valley… Although he dismissed Renwick’s experience, Glendon has one of his own when an unseen something seems to push him aside; he, too, has difficulty walking on. Finally, an exhausted Renwick drops back, leaving Glendon to go on alone. The botanist’s own weariness vanishes when, from the lip of a crevice, he is able to see through his binoculars the unique plant he is seeking, in full bloom in the moonlight. He hurries down to it and begins collecting a specimen – unaware that he is being watched from the rocks… As Glendon works, he notices a strange shadow cast across the rocks nearby, seemingly of an animal but on two legs. Even as he peers into the darkness, Glendon is attacked by a man-sized creature. After a desperate struggle, he manages to draw his knife and fight it off, but not before he is bitten badly on the arm. The creature limps away, and Glendon, in spite of his own injuries, finishes collecting his specimen. Back home in London, in the private laboratory attached to his lavish home, Glendon works on the creation of artificial moonlight, trying to stimulate the blooming of the Mariphasa lupina lumina which has so far refused to flower at all in any conditions. He is oblivious to the gathering hosted by the Botanical Society in the grounds and conservatories of his house, until his wife, Lisa (Valerie Hobson), almost drags him out to their guests. In particular, Glendon tries to avoid Lisa’s inquisitive aunt, Ettie Coombes (Spring Byington), but only succeeds in preventing her from pushing her way into his laboratory. Two of the guests at the party are Lady Forsythe (Charlotte Granville) and her grandson, the famous aviator Captain Paul Ames (Lester Matthews), who is a childhood friend – and old flame – of Lisa’s. She introduces him to Glendon, who is unable to conceal his immediate feelings of jealousy. Later, another party guest accosts Glendon and introduces himself as Dr Yogami (Warner Oland), a fellow botanist. He intimates to Glendon that they have met before, just once – in Tibet – and asks if he was successful in obtaining a specimen of Mariphasa lupina lumina, as his own all died on the journey home. Glendon is reluctant to talk about it, but Yogami persuades him into a private conversation. When the two men are alone, Yogami speaks to Glendon of werewolves, explaining that the Mariphasa is the only antidote to werewolfery. Glendon reacts with incredulous scorn, but Yogami insists that, to his personal knowledge, there are presently two men in London inflicted by the curse of werewolfery. He then puts a hand on Glendon’s injured arm, adding that the curse can be transmitted by a bite…

Comments: Curious, isn’t it? – how long it can take what eventually becomes regarded as “standard” lore to develop. Released in 1935, the first werewolf movie proper is a strange beast indeed, bearing only a passing resemblance to most of its cinematic descendants. Beyond a bow towards the power of the full moon, Werewolf Of London contains little of what would in time become accepted as part and parcel of the werewolf mythology (most of which was invented for the screen), and nor does it nod towards either European or Native American legends.

In fact—to paraphrase its own anti-hero, Werewolf Of London is a singularly single little film, indeed: a Universal horror movie with very few ties to its stable, written and directed by people with almost no genre experience and with a cast featuring none of the by-now familiar Universal horror movie players. The single exception, though you’d hardly call her a “genre actress”, is Valerie Hobson, who came to Werewolf Of London fresh off her appearance in Bride Of Frankenstein. Otherwise, there is a whole new roster in this film, which serves to strengthen its individual identity, but in its lack of star-power, genre and general, probably also contributed to its comparative failure. It is possible, in fact, to view this film’s much more famous successor, The Wolf Man, as a “re-boot” of the werewolf concept, after this version failed to fly.

In truth, though, the most significant names connected with Werewolf Of London are found much further down the credits. The film’s art direction was by Albert D’Agostino, who later moved to RKO and was responsible for the brilliant atmospherics of the Val Lewton productions. The special effects, meanwhile, were the work of John P. Fulton, also coming off Bride Of Frankenstein.

But the most significant contributor to this film is not listed in the credits at all: the werewolf makeup was, of course, designed and executed by Jack Pierce, in what was not one of the happier experiences of his career. In Henry Hull, Pierce found himself working with someone every bit as difficult and temperamental as he was himself—and who wouldn’t sit still. Pierce’s first makeup concept for this film was much heavier – read, hairier – than the fairly minimalist arrangement that was finally adopted, as demonstrated by the still-extant makeup-test shots. However, Henry Hull rebelled against the necessary hours in the chair, forcing the exasperated Pierce to re-work his elaborate design into something much simpler.

(Not that the original concept went to waste, exactly…)

(Don’t you love how the Swedes made it all about Warner Oland!?)

Although the resulting werewolf-lite approach is a disappointment to some viewers, it is justified by the screenplay of Werewolf Of London. The partially-transformed, two-legged creature that appears first in Tibet and then in London – “neither man nor wolf” – is a logical working out of its premise, and most importantly an avoidance of the trap fallen into by The Wolf Man, which to its detriment toggles between an actual wolf and a hairy man in pants. Furthermore, the climax of Werewolf Of London requires that Wilfred Glendon be recognisable in spite of his transformation—but we shall get to that presently.

One thing about Werewolf Of London that is in line with tradition is that it opens with a scientist Meddling In Things That Man Should Leave Alone. Dr Wilfred Glendon, an independently-wealthy, highly successful amateur botanist is in Tibet to seek yet another rare specimen for his famous collection, the phosphorescent wolf-flower, which blooms only by the light of the moon.

(This film treats the idea of a flower blooming at night as Crocodile does that of a crocodile swimming in the ocean, i.e. with completely misplaced incredulity.)

Glendon suffers the usual warning signs and difficulties, but also as per tradition ignores both the rumblings of his “coolies” (whose “Tibetan” appears to be a mixture of Cantonese and, well, gibberish) and the dissuasions of a priest who hasn’t seen a white man in forty years but just happens to be passing at this crucial juncture. The scientist nevertheless presses on in company with his much-less-enthused assistant, Renwick; and despite some odd – almost supernatural – hindrances, they approach the legendary valley where the Mariphasa lupina lumina is to be found. Exhausted, Renwick drops back, leaving Glendon to forge on alone. A glimpse of his goal is all it takes to infuse him with new energy, and he hurries down into the valley—hesitating not one instant before he starts hauling the rare and precious plant up by its roots.

The journey to the valley has been accompanied by some ominous howling, and now, as Glendon digs around, a shadow is cast upon the rocks behind him…

(We get our first glimpse here of one of the film’s two werewolves, just the pointed ears and the hairy forehead, as the creature lurks behind a rock and watches Glendon at work, and let’s just say that if I looked that silly as a werewolf, I wouldn’t show myself either.)

The scientist finally notices the shadow, turning around apprehensively and backing away. As he peers up through the darkness, the creature – resembling a man, and dressed in man’s clothes – hurls itself upon him.

The two struggle desperately, inflicting injuries upon each other: Glendon is slashed on his face and bitten on the arm, but manages to stick a knife into his assailant’s side; it utters a distinctly dog-like cry of pain and lurches away.

With an effort, Glendon drags himself to his knees—and crawls straight back to his precious Mariphasa lupina lumina, reaching towards it with his bloodied right arm. He may have just fought a savage battle for his life against a supernatural being, but he’s a scientist, dammit! – work before bandages. (A rabies shot might be in order, too.)

Cut to London, and to the luxurious basement-laboratory that every movie scientist possesses as a matter of course.

(Speaking of “a matter of course”, Glendon’s lab has both an electrical arc generator and an impressive collection of beakers and flasks belching dry-ice fog: just what every botanist needs!)

The screenplay becomes a little obscure here, but it seems that having tried and failed to coax his wolf-flower to bloom by actual moonlight, Glendon has, with typical scientific overkill, designed and built an artificial moonlight generator—which, of course, a botanist would know perfectly well how to do. However, so far this too has failed, with the wolf-flower buds remaining unresponsive.

More SCIENCE!! – Glendon has a surveillance system, which buzzes when he’s about to be interrupted, and a little video screen that can show him who by. In this case, it’s Glendon’s wife, Lisa—which brings us to an aspect of this film that is both a help and a hindrance.

The most Universal-like thing about Werewolf Of London is that it doesn’t seem quite certain of when it is set: a phenomenon most famously manifested in the Frankenstein films, with their Mittel European torch-bearing mobs wearing spiffy thirties suits and hats.

Here, in addition to a couple of comic relief old biddies who seem to have wandered in off the set of Gaslight or Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde, and the boater-wearing lab-assistant Hawkins, who might be Edwardian, we have the character of Wilfred Glendon himself, who gives every indication of being a relic of the 1890s—from his sternly repressed demeanour to his pince-nez to the fact that he keeps on his high stiff collar and tie even when he’s in his dressing-gown and supposedly relaxing.

Of course, Henry Hull was a relic of the 1890s, inasmuch as he was born in 1890: there was a twenty-seven year age-gap between himself and the eighteen-year-old Valerie Hobson, which is disconcerting yet oddly effective; Wilfred and Lisa really do seem like the products of different eras, whether or not that’s what was intended.

More problematic is the casting of Lester Matthews as Wilfred’s “younger” rival. He was younger than Henry Hull—but only ten years younger, making him seventeen years older than Valerie Hobson, even though Lisa and Paul supposedly grew up together. Henry Hull actually carries his age better than Lester Matthews, who has a receding hairline and bags under his eyes that no-one bothered to conceal. He is clearly much older than his “childhood friend”, with the stated age difference of six years fooling nobody, and this undermines the sexual basis of Wilfred’s jealousy.

Henry Hull is both the alpha and omega of Werewolf Of London. He was notoriously contemptuous of the entire project and behaved like a royal pain on-set, even aside from his tantrum over the exigencies of the makeup chair. He certainly took no pains to hide his feelings from the camera…but bizarrely, this actually adds to his characterisation, setting up Glendon as someone riding hard for a fall; not merely in the usual sense of scientific scepticism, but as a man whose predominant attitude to almost everything – and everybody – is condescension. So certain is he of his fundamental rightness that when this most incredible of tragedies strikes him it hits him on his most vulnerable point: he is unable to admit what is happening even to himself, let alone ask someone else for help.

But it is clear enough, whatever we make of the marriage in toto, that Glendon does sincerely love his wife. Once overtaken by fate, it is the danger to her rather than that to himself which dominates his thoughts and actions. Such is his character, however, that negative expressions of his feelings come to him more easily than the positive, which only serve to drive Lisa away.

Indeed, when it comes to his marriage Glendon strikes us a man who can’t quite believe his own good fortune – and who on some level is simply waiting for things to go wrong.

When Lisa’s “childhood friend” turns up, Glendon is immediately consumed by a jealousy that effectively creates a self-fulfilling prophecy. Here, though it is effective in other ways, the film’s subdued makeup goes some way towards undermining its theme: the buttoned-down Glendon never quite becomes the ravening beast that all those repressed emotions would suggest is in there somewhere.

(It doesn’t seem that Lisa married Glendon on the rebound, exactly, and certainly she cares for him enough to be hurt by his neglecting her for his work; yet the marriage remains a mystery of sorts. Lisa herself remarks that she knew what she was letting herself in for, “Marrying one of the black Glendons of Malvern”, which hints at an intriguing back-story for Wilfred that entirely fails to manifest itself.)

Lisa hauls her reluctant husband out of his laboratory – he’s wearing morning dress under his lab-coat – and into the midst of what we take to be a fundraiser for the Botanical Society, in which Glendon’s collection of rare plants, particularly his carnivorous plants, is the star attraction.

Glendon tries but fails to evade Lisa’s Aunt Ettie, who is another of this film’s odd touches. In any other film, Spring Byington’s Ettie Coombes would be the Odious Comic Relief, and while she is that here, she’s not just that. For one thing, she’s capable of serious malice, expressing her evident dislike of Wilfred by deliberately stirring up trouble in the Glendon marriage. She is quick to recognise Wilfred’s jealousy of Paul Ames, and immediately starts stoking the fires by aiming a series of rapid jabs at his sore feelings. Ames, for his part, is disturbed by the subdued spirits of the girl he remembers as always lively and laughing, although he cannot get Lisa to admit that anything is wrong.

We learn in passing that Ames is a famous aviator, who now owns his own flying-school in California, where he has settled. Wilfred’s pointed inquiries as to when he intends to return there do not exactly help ease the rising tension.

From my own point of view, Werewolf Of London’s most horrifying scene follows. We’ve already seen Wilfred’s Venus fly-traps in action, and now, for the benefit of the gawping onlookers, a rather extraordinary-looking, tentacle-waving plant referred to vaguely as “that horrible Madagascar plant”, notorious for eating “mice and spiders”, is given its dinner—having a nice, fat frog dropped into its maw.

NOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

(While there are, of course, species of pitcher plant that can and do devour small animals, this writhing nightmare is clearly someone’s artificial invention, which gives me reasonable hope that the frog survived its appearance in this film.)

One of the party guests is so disgusted by the “Madagascar plant” that he storms off, venting to the first person he encounters and calling Glendon a “heretic” for bringing such a “beastly thing” into “Christian England”. The Japanese gentleman to whom he expresses these opinions bows and replies gently, “Nature is very tolerant. She has no creeds.”

This is Dr Yogami—with the Swedish Warner Oland playing an Asian character yet again. (WTF, Hollywood!? I mean, seriously, WTF!!??) The embarrassed venter scuttles away, and Yogami goes looking for Glendon. He introduces himself as a fellow botanist and praises the collection, but quickly turns the conversation to the Mariphasa, intimating that he, too, was recently in Tibet in search of a specimen.

(There is an absolutely classic glitch here: Warner Oland says “Mariphasa lumina lupina”, rather than the previously established “Mariphasa lupina lumina”. He hesitates before he does it, too, clearly uncertain as to which ‘l’-word comes first. Director Stuart Walker apparently didn’t think the error was serious enough to warrant a re-take; not anticipating the distant advent of obsessive-compulsives with subtitles and a pause button.)

Glendon is bothered by Yogami’s insistence that the two of them have met before, wary of his interest in the wolf-flower and, in short, eager to escape from this unnerving newcomer. Yogami gently persists, though, and when we catch up with the two of them again, the conversation has moved on to—werewolves…

Another bit of oddness occurs here, although (in spite of appearances) we can’t blame this one on Warner Oland, as it crops up again later: the technical term for werewolfery used by Dr Yogami is lycanthrophobia (which I guess would be the fear of turning into a werewolf, which isn’t wholly unreasonable). Yogami also lays out for us the nature of the creature in question:

“A werewolf is neither man nor wolf, but a satanic creature with the worst qualities of both.”

Unmoved by Glendon’s scoffing, Yogami asserts that to his own personal knowledge, there are in London at the moment two men afflicted with werewolfery. At his supercilious worst (though I can’t help admiring his turn of phrase), Glendon then inquires how one would go about contracting “this medieval unpleasantness” – and has the superior smile wiped off his face when Yogami replies, via a bite… The Mariphasa is the only antidote to the condition, he continues, and without the flower, both men are doomed…

At this critical juncture, Lisa interrupts the conversation. Yogami gives her a thoughtful look, but says nothing more before her.

Whatever he is now thinking, Glendon returns to his experiments, and succeeds in coaxing the Mariphasa into bloom: just a single flower. He reacts with triumph, certain that the other two buds will open in the next few hours; while his assistant, Hawkins, who has conceived a superstitious dislike of the wolf-flower, looks on in dismay.

Just at this moment, however, Glendon happens to glance down at his own right hand—which is covered with hair…

Getting rid of Hawkins, Glendon quickly snips free his single Mariphasa bloom, and squeezes the juice from its stem onto his hand. The hair vanishes as mysteriously as it appeared.

(Since this is the middle of the afternoon, we must assume than the rays of the artificial moonlight generator were powerful enough to trigger this partial transformation, even though – as we later learn – it should only happen at night.)

Upstairs, Lisa is hosting a tea, hoping – vainly, it need hardly be said – that at some point her husband will join the party. Ettie is there, anticipating her own house-warming party that evening in her perverse new digs – “In the midst of the slums, murderer’s dens on one side, pubs on the other.” Lisa begins to explain her doubt that she will be able to get Wilfred to attend, prompting an impatient suggestion from Ettie to forget Wilfred. She further encourages Lisa to allow Paul to escort her. Dr Yogami is then announced; he asks to see Glendon, but Lisa tells him that this will not be possible. Ettie pounces upon the newcomer and insists that he, too, attend her party.

Lisa escorts her other tea-party guests out, leaving Yogami alone for the moment. In spite of the denial, he heads for the laboratory, where the security system alerts Glendon to his presence. He hurries out to head Yogami off, suggesting that he come back another day, only to be told that “another day” will be too late: this is the first night of the full moon.

Yogami’s eyes rest sadly on Glendon’s exposed scars, prompting the scientist to roll his sleeves down in a suggestively hurried way.

Waving aside the other’s stubbornly professed disbelief, Yogami clarifies that the Mariphasa is not a cure for werewolfery, merely a temporary antidote which must be repeatedly applied; multiple blooms are therefore needed. However, when Glendon maintains his pig-headed attitude, Yogami gives up and prepares to leave—then turns back with a warning that the werewolf is instinctively driven to kill the thing it loves best…

Having fore-grounded this ominous and overarching bit of dogma, Werewolf Of London goes on to clarify its underlying mythology. We next find Glendon consulting the traditional “quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore”. He carries the old book to his desk where, amongst the clutter, we find a small tabby-cat comfortably ensconced upon a small cushion and dozing peacefully under the warmth of the lamp.

Well, that settles it. Don’t ask me to dislike Glendon after that, whatever his social and attitudinal failings. We know at first glance that is in fact his cat, and not Lisa’s (she’s the doggy-horsey-landed-gentry type), and that not only is it a regular fixture on the desk but – as is so very often the case – that it is at perfectly liberty to sleep wherever it chooses to do so.

Glendon’s old book is surprisingly specific about the parameters of “lycanthrophobia”, providing such helpful details as the fact that transformation always takes place between nine and ten o’clock on the nights of the full moon; that the juice – or “essence” – of the Mariphasa blossom must actually be injected by inserting the tip of the thorn that accompanies each flower into the skin of the wrist; and that if the werewolf does not kill, it will not re-transform. This exceedingly informative tome also offers up the fascinating factoid that the technical term for man-werewolf transformation is transvection.

Well! – there’s one for the geneticists to ponder.

Glendon’s reading is interrupted by Lisa and Paul; she tries once more to talk him into accompanying her to Ettie’s party, but (having just sat through dinner with the two of them) he responds snidely that he’s listened to enough childhood memories for one night, thank you. Trying to smooth things over, Lisa tells him that she has had the brocade he bought her made up, and switches on the light to show him her outfit.

The result is hardly what she anticipated: Glendon reels back, his hands over his eyes, snarling at her to turn the lights out again. In the dimness once more, he pulls himself together and apologises, excusing himself by explaining that he has drops in his eyes and the light causes him pain.

The double rejection is too much for Lisa, however, and she bids her husband a cool goodnight. As she and Paul turn away, Glendon impulsively calls her back. He hesitates for a moment, then takes her in his arms and kisses her passionately—but she is quite unresponsive…

As Glendon shuts himself into his study, a clock chimes a quarter past nine—prompting him to cast an involuntary glance at his hands. There’s nothing there – Of course not, you can almost hear him thinking – and he drops into a chair on the far side of the desk, casting on his cat the look of a man in need of a consoling cuddle. The cat turns its head and blinks at him sleepily—

—and in instant, turns into a hissing, spitting ball of fury. It snarls and strikes at Glendon, who stares at it in bewildered distress, before scrambling away and fleeing room.

And because they went to the trouble, in a few simple shots, to set up the relationship between Glendon and his cat, this short interlude is genuinely upsetting. This isn’t just some random animal reacting to Glendon, as we are accustomed to seeing in films of this kind: this is his own pet. Being rejected by his wife is one thing, but this—this hurts.

(And I am pleased to be able to report that, in defiance of the usual cinematic convention, the cat makes it safely out of the film. So much for Glendon killing the thing he loves best, hey?)

(What—Lisa? You think?)

However, Glendon has little time in which to reflect upon this personal tragedy: the calming hand that he stretched out to his pet, to which it reacted so violently, is now covered with hair…

While later on Werewolf Of London does include the kind of stop-frame transformation scene that would later become standard in werewolf movies, this first transformation of Wilfred Glendon is wonderfully clever and effective—mostly because it is also wonderfully simple: the frightened, staggering Glendon passes behind a row of columns, and each time he re-emerges, he has transformed a little more.

Glendon’s uncertain steps take him to his laboratory – no more refusal to believe, we notice – but what he does not know is that, earlier in the evening, there was a break-in. Both of the newly-opened buds have been taken; only one more, as yet unopened bud remains. The transformed Glendon can only stare in horror at the severed stems…

…and then his new animal nature takes over. An image lodges itself in his mind – Lisa – Lisa leaving the house with Paul Ames. Growling angrily, he prepares to follow them…

(…and in a single bit of misjudgement, the film almost completely undermines its successful build-up to this moment: before setting out, werewolf-Glendon stops to put on his coat and a cap.)

At her house-warming party, a squiffy Ettie welcomes Lisa and Paul, and introduces to each other Dr Yogami and Sir Thomas Forsythe, who is Lady Forsythe’s son and Paul’s uncle—and the Commissioner of Scotland Yard. This time, it is Sir Thomas who insists that he and Dr Yogami have met before…

Eventually, Ettie gets so soused that Paul and Lisa have to escort her up to bed. Around the same time, the party is disturbed by a howling noise somewhere outside. Everyone agrees that it’s not just a dog—but then, what is it, in the middle of London?

(As much of a pain as he was in other respects, Henry Hull did lend himself to this film’s vocal effects, which blend his own voice with the actual howling of a wolf in an oddly personalised touch.)

Sure enough, werewolf-Glendon is prowling outside; he begins to scale the gates, clambering up onto the balcony outside the room in which Ettie is recovering. She wakes and sits up, staring in disbelief—and screaming…

At this point, Werewolf Of London takes on an annoying (although not unfamiliar) air of classism, with upper-class ladies repeatedly being threatened, but working-class women (including “working girls”) ending up as the actual victims. It is doubly exasperating in this case because, whether Glendon is aware of it or not – and he is at least aware of her hostility – Ettie has gone out of her way to cause him unhappiness. She “asks for it” as much as any of the other victims, yet the screenplay lets her off with a bad fright.

A woman walking home alone in the nearby streets is not so fortunate. When she first sees the figure of a man huddled in a corner, she casts an interested eye upon him—until he reveals his face to her…

One of the more amusing movie newspaper mock-ups I’ve ever seen follows. Underneath the imposing headlines – MYSTERIOUS GOOSE LANE MURDER – UNIDENTIFIED GIRL HORRIBLY MANGLED – sits the following remarkable bit of journalism:

With two unsolved murders on their hands, police of Scotland Yard are today working on the theory that the killings have been done by a very prominent man who is suffering from werewolfery, an affliction which changes him into a man-eating beast at night.

Fantastic as this may sound, police say they have been in conference with scientists who declare there are two men afflicted in London. An intensive search is now being conducted for the strange man who is believed to be half man and half wolf.

I hardly know where to start. I can only suppose that, in keeping with many of its ilk, and perhaps reflective of its clutch of uncredited co-writers, Werewolf Of London underwent some extremely significant and ongoing revisions before it finally hit the screen.

That—or whoever wrote this report had been imbibing too liberally the Nut Brown Ale prominently advertised on the front page of the London Dispatch.

In any case, there has certainly only been one murder in this version, and we cut to Dr Yogami sadly contemplating the headlines. Before him sit the two stolen Mariphasa blooms, one used up and dead, one still fresh—so presumably he wasn’t on the prowl the night before.

Meanwhile, we get some unwelcome comic relief in the form of the stout, middle-aged bobby who was – eventually – the first on the scene of the murder. Paul Ames is visiting his uncle at Scotland Yard, and exclaims that Goose Lane is quite close to Ettie’s house. In spite of the howling, and the nature of the victim’s wounds, Sir Thomas and Paul agree that an actual wolf couldn’t have been responsible, not in London; but then, what did enter Ettie’s room?

Surprisingly, Paul then suggests a werewolf, overriding his uncle’s scoffing with an account of a series of murders in the Yucatan that were always preceded by howling—and which stopped when something was shot as it was slinking through the hills.

Dismissed by Sir Thomas, Paul’s thoughts turn to Lisa. He suggests a moonlight ride to her, which goes over like a lead balloon with Wilfred for about sixteen different reasons, though he responds only with a terse refusal to join the party. A glance at the newspaper puts the seal on his mood.

Lisa finally forces a conversation about their growing estrangement on her husband, commenting that she didn’t used to mind so much being neglected for his work, because his work used to make him happy; but now—now he’s just miserable. Now he almost frightens her – a comment that gets a voluntary protest out of Wilfred – and he’s short-tempered with her, which he never used to be.

Glendon blunders into makes a jeering reference to Paul, but retracts and apologises immediately, begging Lisa to bear with him a little longer. He even promises her that he will come riding, although in that, we fear, he is fooling himself. In fact, he’s hoping against hope that the final bud will open, but the thing remains stubbornly closed…and the moon will soon be rising…

Lost in his own problems, Glendon can see only the potential danger to Lisa, but in his anxiety to get her home safe before the moon rises, he takes the worst possible approach—and causes a head-on collision between 1890 and 1935 by using that most anathematic of words, forbid:

Lisa: “I plan to ride, Wilfred, and I intend to ride! I shall ride tonight, and tomorrow night, and the next night—in fact, every night there’s a moon!”

Not that husbands didn’t sometimes get that reaction in 1890, too.

An unnecessarily lengthy comic relief [sic.] sequence follows featuring the two historically misplaced old biddies, who rent rooms and swill gin together. Never mind that. The upshot is that in an effort to protect Lisa, and perhaps avoid killing altogether, Glendon flees to a disreputable corner of London and rents himself a room. (The suggestion here seems to be if he does kill, at least it will “only” be a lower-class person.) Led upstairs by Mrs Moncaster, Glendon is asked by his temporary landlady if he is “a single gentleman”:

Glendon: “Singularly single, madam. More single than I ever realised it was possible for a human being to be…”

(Mrs Moncaster responds to this with a burst of – almost poetry – a paean to domestic violence – which is more truly bizarre than anything to do with the film’s central premise.)

Once locked in his room. Glendon begins to pray fervently, begging to be kept from transforming again. In what seems a touch of either cynicism or cruelty – or both – he immediately does begin to transform. (Of course, his choosing to sit in the in-streaming moonlight probably didn’t help.) This time the effect is executed using the standard stop-frame technique. Werewolf-Glendon then hurls himself through the closed window (!) of his second-floor room (!!) and sets off into the night.

We cut to the zoo, where the night-watchman, Alf, a married man, is carrying on with a local floozy, Daisy (Jeanne Bartlett, in her only acting role – she later became a writer – doing an hilariously exaggerated “vamp” act, and demonstrating conclusively that a Cockney accent was beyond her). “I hadn’t ought to do this,” Alf comments, doing it, as the zoo’s wolves howl in seeming protest.

Not much to our surprise, werewolf-Glendon is lurking in the vicinity of the wolves’ cages, one of which he sets about unlocking; whether this is an act of fellow-feeling or an attempt to create an alibi isn’t immediately clear. (The released wolf does a better job of looking “savage” than the ones in Wolf Blood – just – although when it hops out of its cage, it just looks frightened.)

Daisy then helpfully sets about signing her own (Hollywood) death-warrant:

Daisy: “You don’t love your wife and your kids—you love me! Tied to a whimpering, white-faced scarecrow of a woman! – you’re going to leave her and come with me, ain’t ya?”

More howling distracts Alf, or maybe he just doesn’t want to answer Daisy’s question. Anyway, he runs off towards the wolves’ cages, leaving Daisy on her own…

The following morning finds Dr Yogami gazing at the second of his stolen wolf-flowers, now also used up and dead. In an unexpected move, he goes to Paul, who takes him to see Sir Thomas, apoplectic over the second murder and his men’s lack of progress. Paul introduces his companion as, “Dr Yogami of the University of Carpathia” (!!!!), and Yogami tells Sir Thomas that they have indeed met before, as he suggested, seven years earlier, when he (Yogami) tried to enlist Scotland Yard’s assistance in a case involving, “An unfortunate mortal afflicted with lycanthrophobia.” (Presumably himself, though he never actually says so.)

Sir Thomas scoffed at him then—and he scoffs at him again now, when Yogami tries to convince him that there will continue to be murders committed under the full moon, unless the authorities seize the Mariphasa plant from Dr Glendon and learn how to cultivate and use it. Sir Thomas is dismissive, apparently having convinced himself that the escaped wolf is responsible for the killings—and he is not best pleased when Paul (on the alert since the mention of Glendon) points out that the wolf only escaped last night and couldn’t have been responsible for the first death.

Glendon himself creeps home – sheepishly, as it were – to check on the remaining bud, which is still refusing to cooperate. Hawkins offers the consoling thought that surely it will only need another twenty-four hours – one more night – prompting a marvellous newspaper-montage sequence, as a despairing Glendon goes from thinking about the current headlines to imagining future headlines, which report to the world the police pursuit of himself—and Lisa’s gruesome death…

Pardon me for a moment – you know how I love movie newspaper mock-ups! – although I don’t think these are mock-ups as such, but rather real newspapers with the lead stories replaced and the rest left intact.

There’s much to love about these brief intrusions by the fourth estate, including the ubiquitous alcohol advertising; while conversely, the frequency of reported aeroplane-related accidents is rather worrying; though I think my favourite touch here is that in “seeing” his worst fears plastered all over the headlines, Wilfred allows the bloody slaughter of his wife to share the front page with the fact that South Africa were 5-39 after suffering batting disasters on a soft pitch.

(Oh, and fun fact: they were still spelling clue “clew” as late as 1935.)

Leaving Hawkins – who clearly thinks he’s cracking up – to nurse the “stubborn Mariphasa”, Glendon runs away again, this time to Falden Abbey, the country estate which belongs to Lisa, and where she grew up. (The caretaker’s dog wags its tail at Glendon, who is almost pathetically grateful; but then of course, the moon isn’t up yet…) This historic building has a desirable feature in the form of a cell known as “the Monk’s Retreat”, into which Glendon arranges with the bewildered Timothy to be locked for the night—no matter what he then says or does.

However, as a cruel fate would have it, Lisa and Paul have decided to drive down to the scene of so many of those “childhood memories” that offended Glendon so, a “last glimpse” for Paul prior to his imminent return to America. Leaving the car in the road, they take a shortcut across the lawn in the light of the rising full moon, which both triggers Glendon’s transformation and allows him a perfectly clear view of a scene guaranteed to fuel his raging jealousy.

Perhaps it’s fortunate that he wasn’t also in a position to hear their earlier conversation, in which Paul declared his undying love to Lisa and told her that’s it’s obvious that she’s miserable. Interestingly, a certain suspicion seems to have wormed its way into Paul’s consciousness, as he confesses to being frightened for Lisa.

However, she rejects both his fears and his love, though gently, and challenges him to a race across the lawn—directly beneath the window of the Monk’s Retreat, the iron bars of which were not, evidently, designed to withstand the fury of a werewolf in love.

As Lisa waits for Paul at Monk’s Tower, werewolf-Glendon appears through the bushes. She screams as he attacks her, seizing her by the throat—which, in a very rare movie touch, actually stops her screaming. Paul rushes up and Glendon drops Lisa in order to attack him instead. He tries very hard to bite him – nasty, Wilfred! – but Paul manages to break free and clubs him down with a heavy branch. Being most concerned with Lisa’s safety, he carries her away, leaving werewolf-Glendon where he lies.

The next day, Paul reports to Sir Thomas, finally telling him that there was something “grotesquely familiar” about the creature; that it was, in short, Wilfred Glendon. Sir Thomas is incredulous, but finally agrees to go to Glendon Manor – where Lisa and a chastened Ettie are locked in together – to investigate. However, he is stopped in his tracks by the report of another murder, this time of a chambermaid at the Bedlington Hotel, some 150 miles from Falden Abbey. Sir Thomas takes this as proof that Glendon could not be the killer (although he has no explanation for the reported transformation), and insists on going to the murder scene before calling at Glendon Manor.

Of course, what they find out at the scene – apart from the fact that the room “smelled like a kennel” (!) – is that is has been occupied by Dr Yogami. As Sir Thomas inspects the body, Paul finds two dead wolf-flower blossoms in the bin – last night being the third night – and puts two and two together. By this point even Sir Thomas is convinced, and the men set out again for their original destination.

But there is no sign of Wilfred Glendon—nor any of Dr Yogami. A police net is cast for both men. Hawkins, in the laboratory, is startled by a knocking sound, and admits Glendon via a trap-door from a secret passage…which is of course just what every botanist needs. He reports that the Mariphasa has not bloomed, but shows definite signs of doing so. Immediately, Glendon rushes to inspect it, not noticing that someone is creeping down the stairs towards him…

(We are given no hint of how Yogami got in.)

Just then, the flower does open, to Glendon’s infinite relief. He goes to harvest it, but – scientist that he is! – decides that he needs to wash his hands before taking his “injection”. As soon as his back is turned, Yogami slips across, cuts the flower—and uses it.

Glendon: “Yogami! You brought this on me that night in Tibet!”

Yogami: “Sorry I can’t share this with you!”

But he is only halfway up the stairs when Glendon – not transformed – grabs him. Yogami breaks his walking-stick across Glendon’s shoulders, but the scientist gets hold of his throat and drags him down. The two become locked in a deadly battle, but since Glendon transforms mid-fight, Yogami never really stands a chance. And as his rival dies, werewolf-Glendon howls in triumph…

(If a werewolf bites another werewolf, does it turn into a human?)

The sound of the fight reached Lisa and Ettie, locked in upstairs, and so does the howl. They catch sight of werewolf-Glendon out on the lawn and telephone to Scotland Yard for help, learning that Sir Thomas and Paul are on their way. Werewolf-Glendon climbs up onto the balcony. The women bolt in the other direction, locking the bedroom door behind themselves and forcing their pursuer to smash his way through it.

Having done so, however, he catches sight of the newly arrived Paul and slips out through a window, stalking him across the roof and dropping onto him as he moves to enter the house.

Paul seems doomed, but werewolf-Glendon releases him when he sees a horrified Lisa watching through a window. He breaks back into the house. Ettie faints, but werewolf-Glendon isn’t interested in her: he only has eyes for Lisa, who backs away in terror from the strange intruder; an intruder she recognises…

Backing slowly up the stairs, werewolf-Glendon only a step away, Lisa begins pleading with her transformed husband: “It’s Lisa – Lisa! Don’t you know me? Wilfred!”

And werewolf-Glendon hesitates…just long enough to get a bullet from Sir Thomas in the back. He tumbles down the stairs to sprawl on the carpet. He’s not quite dead yet, though, and so, perhaps alone amongst his hirsute brethren, he gets to deliver a valedictory speech:

“Thanks…thanks for the bullet. It was the only way. In a few moments now, I shall know why all of this had to be. Good-bye, Lisa. Lisa…good-bye. I’m sorry…I couldn’t have made you…happier…”

Yeah, way to lay a guilt trip on her in parting, Wilfred.

Or maybe not. No sooner have we witnessed the traditional post-mortem re-transformation than we cut to a shot of a small plane in flight—presumably Lisa and Paul on their way to California; a shot than in an odd, amusing touch, blends into the closing Universal logo, with the studio’s own small plane put-putting around the globe…

So what does Werewolf Of London offer up for the connoisseur? An interesting mix of the standard – transmission by bite, the effects of the full moon – and the fresh, including the notion of a medical cure (or remission) for werewolfery; an idea later appropriated by the descendants of The Wolf Man. We learn here that werewolves are not as difficult to kill as we might anticipate, with old-fashioned lead doing the business as well as any fancy-schmancy silver, and that moonlight causes an actual physiological reaction, rather than being a psychological trigger.

In particular, I enjoy the way this film involves a desperate battle between two men to avoid becoming killers; a battle that, ironically, finally turns deadly. Yogami is especially interesting in this respect, as he seems to have no close personal ties, far less Wilfred Glendon’s emotional imperatives; yet after what we know to be at least seven years of affliction, we find him by no means giving up and giving in, but still trying to find a way to avoid his manifest destiny—even if it means resorting to some pretty underhanded tactics. Warner Oland gives a dignified performance here (a bit too dignified: you can’t really imagine him scampering around slaughtering chambermaids), suggesting the weariness of the soul that drives Yogami to pursue the Mariphasa flowers for himself, regardless of the consequences to Glendon and Lisa.

And yet Werewolf Of London was not a success—not to anything near what I think its inherit merits deserve, although it is certainly not without serious flaws, including an all-too-typical over-deployment of comic relief. Yet I doubt that was the problem. Far more likely, audiences found it hard to warm up to what is, admittedly, a fairly chilly central performance from Henry Hull, whose Wilfred Glendon is certainly more understandable than actually likeable. That said, those of us who share his tendencies towards introversion and social awkwardness – and cat-coddling – will not find it too hard to empathise with his sufferings, both marital and lycanthropal.

Harder to deal with, perhaps, is the dearth of sympathetic characters surrounding Wilfred Glendon. There is insufficient balance in the depiction of the Glendon marriage, so that Lisa ends up being part of the problem rather than one of the film’s victims. Her situation is not a happy one, granted, but neither is her response to it, which is to spend most of the film, if not encouraging, then certainly not discouraging the attentions of Paul Ames, who in turn does his best to break up the Glendon marriage. Meanwhile, Sir Thomas is a pompous know-it-all, and Ettie Coombes is—well, never mind the epithets.

In fact, the only character in this film other than Wilfred Glendon who it is possible to sympathise with is the other werewolf. As you would know, I nearly always side with the monster in any given film; it occurs to me that perhaps my over-fondness for Werewolf Of London stems from the fact that it pretty much forces everyone else to do so, too.

But the film is what it is—and what it is, is one of the “forgotten” Universal horror movies. On the other hand, even people who don’t watch horror movies, or don’t like “old movies”, have a fair idea what we’re referring to when we start babbling about the cosmic injustice associated with men who are pure at heart and say their prayers at night. This degree of persistent pop cultural cachet suggests that the makers of The Wolf Man succeeded in what must certainly have been their intention, to correct the faults of Werewolf Of London, including the big one of being “a bit cold around the heart”.

It is curious, and a little daunting, though, to consider that if Werewolf Of London had been a success, it would have sent the cinematic evolution of the werewolf story in quite a different direction – depriving the world not only of The Wolf Man, which certainly would not then have been made, but also of the later film’s myriad descendants: the sequels, the monster mash-ups, and even the comedies – and I wouldn’t give any of those up for anything.

Okay, maybe the comedies…

Want a second opinion of Werewolf Of London? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review is part of the B-Masters’ examination of werewolves on film.

Ah yes, the old Venus Frog Trap. Not enough tentacles, though.

“obsessive-compulsives with subtitles and a pause button” – and we love you for it. (There are some people who really don’t see that sort of difference as important, or a problem, no matter in what field of endeavour. They are wrong.)

“transformation always takes place between nine and ten o’clock on the nights of the full moon” – does it observe summer time?

I wonder whether the coat-and-cap could be regarded as suggesting that Glendon isn’t really as out-of-control as all that; that, like Hyde, the jealousy and violence were always part of his nature, rather than being just an externally-imposed curse. But that’s not really of a piece with the rest of the film, and one would probably be reading too much into a casual gesture.

Ah, the University of Carpathia! Surely the second-best place in the world (after good old Miskatonic) to study mediaeval metaphysics!

The “clue” spelling exists by 1590, so that’s a pretty good run for two versions in parallel. Google Books ngrams suggests “clue” was about 4× as popular from 1800 onwards, with “clew” declining from about 1880-1900, and for some reason “clue” exploding in popularity in the 1990s. British English seems largely to have switched over from about 1840.

(“Why must I be a lycanthrope in love?”)

LikeLike

They are wrong.

You are right! 😀

There’s actually a long history of emotional scenes ruined (to us) because someone stops to put a hat on before storming out or running away. It’s hard to imagine now how absolutely compulsory it was to wear a hat; how not wearing a hat would draw attention, and so if you were running from something, you’d be remembered. I guess this is similar, but it does spoil the moment.

“Clew” is one of the little things I look out for: it was strangely persistent.

A few days of threatening the one you love vs years of killing strangers— I’m still going to give Yogami the anti-prize (as per Dawn’s comments).

LikeLike

Wow, no silver bullet needed? That makes it a lot easier to kill.

I think the most significant (and frightening) difference is mentioning that if the werewolf doesn’t kill, he stays a werewolf. That would indicate that Yogami must have killed at least 252 people, since he’s been afflicted for 7 years. The idea that one MUST kill or else is the stuff of nightmares.

LikeLike

Yes, the film never really goes there but the implication is clear enough. Perhaps that was one of the things they revised away from, as just too horrifying / depressing?

LikeLike

Given that there were two lycanthropes in the movie, shouldn’t it have been titled “WereWOLVES of London”?

(cue Warren Zevon…….)

LikeLike

well, you could say that one was OF London, since he was English. There were 2 werewolves IN London. I guess the other one wasn’t worthy of mention in the title.

LikeLike

Dawn is right, I’m sure: the other one is a FOREIGNER, after all.

(I was Warren Zevon-ing all through this!)

LikeLike

This long-time Babylon 5 fan saw the first photo of Warner Oland’s wolfman and immediately exclaimed: “Zathras!”

LikeLike

Ooh, yes!

LikeLike

I just caught this on Svengoolie (don’t judge me!), and the host had a comment about the rumor that Hull changed the makeup because he didn’t want to sit in the makeup chair for that long. According to Hull’s grandson (I think), it was really because Hull thought the original makeup wouldn’t have allowed for Lisa to recognize him, as required in the script. The implication by his grandson was that Pierce resented the change so much that he spread the rumor about Hull not wanting to sit in the chair that long. Pierce did refuse to let any pictures be taken of him working on Hull.

Hull may have had some tantrums during the movie, but apparently this wasn’t one of them.

something else, at the beginning of the film, Dr. Yogami definitely says that there are 2 werewolves currently in London. Was he counting Glendon? I guess he would know since he was the one who bit him in the first place.

LikeLike