“I may not look it, Madame, but I was once a very successful banker. Three men – my partners – lied and tricked me into prison. Well—three lives are going to pay for it…”

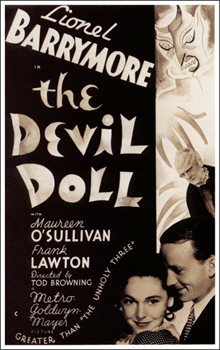

Director: Tod Browning

Starring: Lionel Barrymore, Maureen O’Sullivan, Rafaela Ottiano, Grace Ford, Henry B. Walthall, Robert Greig, Arthur Hohl, Pedro de Cordoba, Frank Lawton, Lucy Beaumont, E. Allyn Warren

Screenplay: Garrett Fort, Guy Endore, Eric von Stroheim and Tod Browning, based upon a novel by Abraham Merritt

Synopsis: Two men make a daring escape from Devil’s Island. One is Paul Lavond (Lionel Barrymore), a former banker framed and wrongly convicted of murder and embezzlement; the other is an obsessed scientist named Marcel (Henry B. Walthall). After weeks on the run, the two succeed in evading the authorities, and reach an isolated house occupied by Marcel’s crippled wife, Malita (Rafaela Ottiano). Marcel is thrilled to find that Malita has been continuing with their work, telling her that he has thought of a way of solving the problem that has been hampering the experiments. Lavond follows Marcel and Malita to their laboratory. There, Malita displays a number of tiny dogs that Lavond assumes are toys. He is shocked when Marcel insists that they are real dogs, shrunk to one sixth of their normal size. Unfortunately, the shrinking process damages the brain of the animals: they cannot think for themselves, but they can be controlled by the will of others, something Marcel demonstrates for the astonished Lavond. Marcel tells Malita that he has thought of a way of preserving the brain during the shrinking process, and goes on to explain his plan of shrinking people, so that their food needs will be similarly reduced, thus combating world hunger. Malita invites Lavond to stay with them, but he reveals his plan of revenge against the three men who framed him, his former partners, saying he must leave soon. That night, Lavond is woken by noises downstairs. He enters the laboratory to find that Marcel has reduced the house servant, Lachna (Grace Ford). However, Marcel’s attempt to preserve the brain has failed: Lachna is like the dogs, mindless, but able to be controlled by the will of another. Marcel is so distraught at this outcome that he suffers a heart attack and dies. In her grief, Malita begs Lavond to stay and help her carry on the work. Lavond initially rejects the offer, but then a plan begins to take shape in his mind. He offers Malita a partnership… In Paris, Coulvet (Robert Greig), Radin (Arthur Hohl) and Matin (Pedro de Cordoba), Lavond’s former partners, meet to discuss Lavond’s escape from prison. They agree to offer a large reward for his capture. The police search is in vain, however: Lavond has indeed returned to France, but has assumed another identity, that of “Madame Mandelip”, a dollmaker with a shop in the Parisian backstreets. In this guise, Lavond visits Radin, demonstrating a “toy” horse and asking him to invest in “her” business. Radin visits the shop, where Lavond shows him Lachna, now dressed as an Apache. Pointing out the detail in the “doll”’s costume, Lavond shows Radin a tiny stiletto—then stabs him in the thigh with it. The knife was dipped in a substance that paralyses its victim. As Malita gleefully contemplates shrinking Radin, Lavond – as Madame Mandelip – goes to see his daughter. Lorraine (Maureen O’Sullivan) is working in a laundry in order to support herself and her grandmother, who is blind. Although she is in love with Toto (Frank Lawton), Lorraine has refused to marry him because of her father’s disgrace, and her mother’s suicide. Lavond visits his own mother (Lucy Beaumont), to whom he has already revealed himself. He tells her that he plans to tell Lorraine who he is, but when Lorraine arrives she speaks of him so bitterly that he changes his mind. Instead, Lavond begins the next phase of his revenge, visiting the home of M. Coulvet, to sell his wife a “doll”…

Comments: I find it an interesting exercise to compare The Devil-Doll with The Walking Dead. Both released in 1936, the films have more in common than you might expect of two productions emanating from, respectively, MGM and Warner Bros., chiefly their very odd mix of tones and subject matter. The difference is that while, against all conceivable odds, The Walking Dead manages to integrate its disparate components – horror, science fiction, crime, religion, romance – into a workable whole, The Devil-Doll fails to find the correct balance; or rather, it doesn’t even try.

To illustrate the problem, let’s try this quick quiz. Three plot elements run in parallel throughout The Devil-Doll:

- Mad science – with the shrinking of people and animals, and a scheme to “make the whole world small!”

- Revenge – with a wrongly convicted man on an obsessive quest to track down and punish the ones who framed him

- Sentiment – with an estranged family reunited

Which of these three do you think the film should focus on primarily? If you said (c), congratulations—you may have a career ahead of you as an MGM executive.

Jokes aside, this really is what’s wrong with The Devil-Doll. It’s got some really good stuff in it – not to mention some really bizarre stuff – but it never gives us enough of it. It is, in the end, the work of its studio and not of its director. This was Tod Browning’s penultimate movie as a director, and it is evident that after the debacle of Freaks, he was being kept on a very short leash. This manifests itself in a distinct unevenness of tone: the film brightens up whenever something odd is happening, but becomes listless and rather forced when the focus shifts to the domestic scenes. In this context, it is ironic and more than a little sad to find listed in the film’s credits another of MGM’s career casualties: Eric von Stroheim.

The Devil-Doll opens promisingly with a hunt for two prison escapees. The script never does spell out its geography, but the men are being hunted through a swamp, and one of the pursuers comments that, “They’ll never make it off the island”, so it’s safe to assume we’re on Devil’s Island. The film’s geographical obscurity continues during the next sequence, as we cut to Paul Lavond and his companion, a man known only as Marcel, arriving at Marcel’s swamp-front home in a small skiff, to be greeted by his wife, Malita, who since her husband’s incarceration has packed up the family business (of which, more anon) and moved to Devil’s Island herself.

We never do find out, by the way, what it was that Marcel was imprisoned for; but given the whole “scientist” thing, I’m going to go out on a limb and guess it wasn’t for tax evasion.

To give this film its due, with the reuniting of Marcel and Malita we see something that the cinema, to this point, had never given us before: Mad Scientists In Love. Indeed, this is among the first genre films to suggest that a scientist could actually be capable of having a normal relationship—particularly when that scientist is still, in effect, a Bad Guy, if not the film’s actual villain.

Equally striking is that Malita is a scientist in her own right, Marcel’s equal, and not a mere assistant; and that although the marriage will eventually come to a tragic end, it is not, for once, because of the irreconcilable differences between Science and Love. On the contrary: from first to last, these two are on exactly the same wavelength. When Marcel arrives at the laboratory / hideout that Malita has contrived for them, the two exchange a single, but deeply heartfelt, embrace – “I knew you’d come here. I knew you’d wait,” murmurs Marcel to his wife – and then it’s straight back to work for both of them.

Rafaela Ottiano’s performance as Malita is unquestionably the highlight of The Devil-Doll. Astonishingly, she not only manages to steal scenes from Lionel Barrymore – no mean feat in itself – but more than once does so while not doing anything. Just standing there, the woman is a riot of exaggeration; but once she starts stumping around on her crutch, pulling faces and declaiming her not exactly subtle dialogue, it’s almost more than the heart can bear. And to top it all off, she apparently patronises the same hairdresser as Elsa Lanchester.

Meanwhile, Henry B. Walthall – a lifetime away from The Avenging Conscience and The Birth Of A Nation – reveals Marcel as one of those scientists perfectly willing to maim, kill and destroy in the name of helping “all” humanity.

Marcel’s particular obsession is the limited nature of world resources; a man ahead of his time, indeed. Arguing that the dinosaurs died out because the world could no longer sustain creatures of such massive size and energy requirement, Marcel reveals to Lavond that the object of his work is to find a way to shrink living beings to one-sixth of their normal size, so that they will need only one-sixth the food.

(Actually, it’s more extravagant than that: he wants to shrink “every living thing”, which strikes me as just a tad…impractical…not to mention counterproductive)

And indeed, Marcel and Malita have already succeeded in their aim—up to a point. The scientists have not yet been able to overcome the [*cough*] one tiny flaw in their scheme, that fact that the shrinking of the brain wipes all memory and autonomy, leaving the subject alive but without volition, able to be controlled by the will of others but capable of no spontaneous action.

However, Marcel thinks he’s come up with a solution – “It came to me one night in that cesspool of stupid minds!” – and so it’s off to the laboratory. Our anti-heroes’ work-space is, I am happy to report, quite delicious, all glass apparatus and tubes and dusty bottles with rubber stoppers and beakers and, yes, Conical Flasks filled with Mysterious Coloured Fluids – about 99% of which turns out to be completely superfluous, except in the decorative sense, since the scientists’ “process” involves nothing more technically advanced than a lot of dry-ice fog – sorry, mist – something in a syringe, and ludicrous amounts of cotton wool.

Lavond, to this point watching and listening in silent bewilderment, breaks out in open scorn when Marcel begins examining what he, Lavond, takes to be toy dogs. Marcel replies that they are, on the contrary, the real deal; and after reacting to Lavond’s scepticism in the traditional way – “You think I’m mad!?” – proceeds to prove his case by reanimating half a dozen tiny canines with the force of his mind: their behaviour is quite normal, so long as Marcel concentrates upon keeping it so.

The special effects in The Devil-Doll are a real mixed bag. Most of the scenes involving shrunken people and animals are done via superimposition, which varies wildly in quality. This first scene with the dogs is probably the worst of it, although there are various other wince-worthy moments later on. On the other hand, an extended sequence realised by having Grace Ford interact with a series of oversized props is brilliantly designed and executed; and there are other, similar scenes that nearly match it for quality.

Having, as he thinks, solved the problem of the brain-wipe, Marcel wants to experiment immediately, but Malita and Lavond insist upon him resting first. Lavond explains to Malita that Marcel’s prison-term affected him badly, and that he has been in poor health for some time.

Now, throughout all these scenes, there have been various glimpses of the scientists’ servant, a girl called Lachna, who is evidently a bit “slow” – or perhaps more than just a bit. In an ominous aside, Malita refers to her as “an inbred peasant half-wit” from “a Berlin slum”. It’s obvious that she and her husband have plans for Lachna, which perhaps they don’t really want to get into in front of their house-guest.

Malita shows Lavond to a bedroom – where there is a glass flask on the bedside table for no readily apparent reason – telling him that he can stay as long as he wants…and help with the work. Lavond thanks her, but tells her he has “work” of his own to attend to in Paris—which, given the nature of it, adds an ironic edge to his outrage and indignation over the inevitable fate of the unfortunate Lachna.

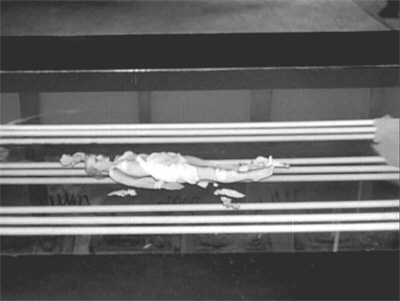

This is revealed when noises downstairs wake Lavond in the middle of the night. He creeps back to the laboratory, where to his horror he discovers the now approximately foot high Lachna lying on a table, swathed in cotton wool.

The Devil-Doll is rather amusingly self-conscious here: unlike most films that deal with shrinking, or embiggening, or some other kind of transformation, and which simply ignore the issue, it is obvious that it was worried about the question of what would happen to someone’s clothes. Lachna here is no longer in her own, but covered – at least, at the critical junctures – in what I’m sure is supposed to be fragments of cotton wool.

Lachna stretches, smiling to herself as if waking from a refreshing sleep; her reactions are swifter, more controlled. Malita exults that Marcel has succeeded in “correcting” her brain, that she is no longer a “stupid half-wit”. But foot-high Lachna is still too big: Marcel orders Malita to turn on the dry i—uh, I mean, the mist, while he starts covering the girl in still more cotton wool. At this point, Lavond tries to intervene:

Lavond: “This is wrong!”

Marcel [blankly]: “Why?”

Eventually, the mist clears. Marcel pulls away the cotton wool, revealing that Lachna is now about eight inches tall…and that she has gone the way of her predecessors: her brain is blank, she is without will.

The shock and the disappointment of his failure, on top of his existing ill health and the strain of his escape, are too much for Marcel: he has a heart attack and dies. And with him, alas, dies the best part of The Devil-Doll.

Malita is shattered by Marcel’s death, but reacts as a good scientist-wife should: “Our work! Our work! We must carry on! You must stay here – you must help me!” she throws at Lavond, “Marcel would want you to!” And barely missing a beat, she’s back to making “mist”, tossing around cotton wool, and doing something to Lachna with a syringe, offscreen—which, given the now-relative proportions of girl and needle, I think we can all be grateful for.

Malita succeeds in shrinking Lachna a bit more and then, cradling the girl in her hands, orders Lavond to concentrate, and give her movement. He does, momentarily, before going into the usual, “I want no part of it!” layperson routine. Malita, however – proving that she’s more on the ball than you might anticipate – offers him a partnership: they’ll move to Paris – you know, Paris – where there are lots and lots of people to experiment on, all sorts of people; bankers, for instance…

Four months later, the French police finally lift their suppression order and admit to Lavond’s escape—much to the consternation of his former partners, Victor Radin, Emile Coulvet and Charles Matin. The former two are in a panic, but Matin declares that Lavond would never be stupid enough to return to France. However, when Radin suggests offering a large reward for Lavond’s recapture, Matin agrees, commenting that it would be “amusingly ironic” to use Lavond’s own money for such a purpose.

But unbeknownst to the conspirators, Lavond is already, not merely in France, but in Paris, where he has assumed a new identity: that of Madame Mandelip, Sweet Little Old Lady.

Lionel Barrymore never was the most subtle of actors. He could, of course, be extremely effective; but it generally took high quality material and a strong director to keep him in check. Obviously, this was a task beyond the capacity of Tod Browning at this stage of his career: once the dress goes on, all restraint comes off. From this point onwards, whether someone enjoys The Devil-Doll or not depends very much upon their reaction to Madame Manderlip—and personally, I find that a very little of her goes a very long way.

(It speaks volumes for the extravagance of Rafaela Ottiano’s performance that even at this stage of the game, she is able to pull our attention away from Lionel Barrymore.)

And with the appearance of “Madame” comes also the intrusion of the sentimental portion of our story. Lavond’s conviction left his family in tatters, stripped of their fortune and publicly disgraced. Lavond’s wife finally killed herself, leaving their young daughter, Lorraine, to be raised by her grandmother, Lavond’s mother.

Currently, Lorraine works as a laundress—setting up a lovely piece of MGM snobbery. It is very evident that we’re supposed to be horrified by Lorraine’s situation, because she comes from what was a good family, and used to be rich. (And besides, she speaks with such a lovely British accent.) At the same time, the film has no sympathy to spare for the other laundresses, who are poor and common: they’re just one of the nasty things that poor Lorraine is forced to deal with.

Another is that her conscience won’t let her marry her boyfriend, Toto Fortuna, a taxi-driver, although he is unbothered by her family troubles. (Of course, without the family troubles, Lorraine Lavond would hardly have crossed romantic paths with an ex-pat Italian taxi-driver…let alone one who also has a refined British accent.) Finally, Madame Lavond is blind, and wholly dependent on her granddaughter. Lorraine complains resentfully that what she earns at the laundry can’t even feed the two of them, and that consequently, she must spend her nights working as a “hostess” at a seedy nightclub. (The script hastens to make it clear she’s not doing anything really wrong, just luring men to buy drinks.) All this has, not surprisingly, left Lorraine with strong and bitter feelings against her father, and she has no inclination to listen to her grandmother’s protestations of his innocence.

Meanwhile, Lavond has started on his campaign of revenge. “Madame Mandelip” and Malita have set up a toy-shop – where at least most of the toys are toys – and Madame calls upon Radin, ostensibly to acquire financial backing for a new line of “voice-controlled” toys.

To demonstrate, she brings with her a small horse, which to Radin’s astonishment seems to obey verbal commands. He is impressed, although he does the usual offhand, don’t-seem-too-eager routine, and agrees to visit Madame at her shop that evening—but insists he’s making no promises. “You don’t have to,” replies Madame, in a parting shot worthy of Bela Lugosi. “Once you’re in my shop, I’ll wager you’ll do anything I ask.”

(By the way, I can only assume that Malita is actually the one paying for all this, experimental horses included. Mad science must have been more lucrative back then.)

That evening, with Radin safely downstairs in the workshop, Madame introduces him to Malita and asks whether everything is ready? Malita, who has just stumped away from some glass apparatus and a pile of cotton wool, agrees that it is. As Madame blathers on to Radin, Malita picks up the tiniest of stilettos and dips it into a Mysterious Coloured Fluid before handing it over. Madame then demonstrates to Radin her newest creation, an Apache doll – the unfortunate Lachna, of course – declaring it to be perfect in every detail. It even comes with its own stiletto—which Madame then plunges into Radin’s thigh.

The banker rises to his feet, then drops helplessly back into his chair, staring in horrified disbelief at the person who now reveals himself to be Paul Lavond. Lavond tells him not to worry, that he’s not going to die. Somehow, neither he nor we are much reassured by this promise…

Two days later, Emile Coulvet is getting panicky over Radin’s disappearance. He contemplates asking for police protection, only to have Matin retort drily that the less they have to do with the police, the better. As Coulvet shows Matin from his house, Madame Manderlip comes in – to show her “special dolls” to Madame Coulvet, who is impressed by their lifelike appearance. “It even feels life-like,” she comments, although this being 1936, she doesn’t follow up with a question about anatomical correctness. (She might have gotten a surprise there, indeed.)

Over the course of the conversation, Madame Manderlip takes a moment to praise the beauty of her customer’s spectacular pearl, diamond and emerald necklace. Between flattery and the chance to own something unique, Madame Coulvet is won over, and purchases the Apache doll for 250 francs—or rather, the exasperated but spineless Monsieur Coulvet does. At this moment, the young Mademoiselle Coulvet returns home with her nurse, and immediately claims ownership of the doll. So it is that when, that night, a mental command comes from Paul Lavond, the reanimated Lachna must struggle free from her “owner”’s arms and negotiate her way out of a crib before she can obey it.

This really is a marvellous sequence. Lachna must escape the child’s room, find her way to the master bedroom, and scale the dresser using whatever she can. Once there, she plunders Madame Coulvet’s jewellery-case – the emerald necklace, of course, and its matching bracelet – and drops her prizes off the balcony outside and into Madame Manderlip’s basket below. All of this is done using oversized props, and it is very nearly flawless in its execution, particularly in the way that the items that Lachna must move are given appropriate weight, so that she must struggle to move them.

Once Lachna moves on to the second part of the plan, however, we’re back in the world of unconvincing superimposition. Carrying the pre-dipped stiletto, she clambers up onto Coulvet’s bed, creeps close to his head, and plunges the stiletto into his neck. His cry wakes his wife, who finds her husband in a strange, half-sitting posture, self-evidently completely paralysed and with his face contorted in terror. As screams shatter the night, outside, Paul Lavond smiles to himself…

Back at the shop, Lavond chuckles over the bafflement of the police and the thought of Coulvet, “Taking up my sentence where I left off”. He goes into the backroom, where he works at prying all the gems out of Madame Coulvet’s necklace, and at length is surprised by the sound of music. Returning to the workshop, he finds that Malita is amusing herself by making the two Apache dolls – Lachna and Radin, that is – dance together.

It occurs to me that it might have been a match made in cinematic heaven (no offense to the departed Marcel intended), if only someone had thought to introduce Malita to Mr Franz from Attack Of The Puppet People.

Lavond is at first amused too, but then Malita lets things get carried away: spinning Lachna around, Radin throws her right off the edge of the table, which breaks Malita’s control, and very nearly breaks Lachna. The partners are having a spat over this when they are alarmingly interrupted by a visit from a police detective, asking questions about Madame Manderlip’s visit to the Coulvet house—and her admiration of the missing necklace. Lavond is so distracted at this point, Malita must hurriedly remind him to put his wig on and to do the voice.

A nice suspense sequence follows. Lavond had unthinkingly carried the small cup full of loose jewels into the room in the first place, and hurriedly set it aside to go to Lachna’s aid; and now, while Madame Manderlip attracts and holds the detective’s attention, Malita must hide the jewels—which she does by pouring them inside a round-bottomed, rocking clown toy, which they usually fill with candy. Naturally, the detective immediately decides that the toy would be perfect for his child…

Having visited Coulvet in hospital, the previous snide and silky Matin is on the verge of a breakdown. He dines with Coulvet’s doctor, and as the two men debate what could possibly have caused Coulvet’s condition, who should wander by but Madame Manderlip? – selling mistletoe for Christmas, ostensibly, but also managing to slip a written note under the bill delivered to the distracted Matin. When he discovers it, he finds that it consists of a list of biblical chapters, verses, lines and words, along with an exhortation to go home and study that Book. He does, translating the code thus: This night tenth hour thou shalt likewise enter the shadow of death confess and be saved.

That’s enough for Matin. He shows the notes to the police – after snipping off the bits about confession, of course – and surrounds himself with the police protection that earlier he sneeringly dismissed.

(The explanation from the detective in charge, as to why all this is happening so close to Christmas, is perhaps my favourite line in the film—and of course you’ll find it over in Immortal Dialogue.)

However – not surprisingly, considering the absolute mystery of the fates of his colleagues – as the tenth hour approaches, Matin’s already frayed nerves begin to give way. Mind you, he doesn’t know what we know: that the miniaturised Radin has already been smuggled into the house…and is hanging from the Christmas tree amongst the other ornaments. Receiving his orders, Radin begins to climb down, and to make his way upstairs.

This sequence is rather interesting, inasmuch as Radin definitely displays autonomy of thought and action: concealing himself when necessary, and so on. Perhaps Marcel succeeded after all, at least to an extent. Radin creeps into the room in which Matin sits nervously, surrounded by policemen; and as “the tenth hour approaches”, so does Radin—stiletto in hand…

Matin, however, snaps; and as the clock strikes ten, he does indeed confess to everything, clearing Lavond completely.

Well—not completely. The final section of The Devil-Doll is by far its most interesting, philosophically speaking. Paul Lavond was innocent – innocent of murder and theft – but in clearing his name he has deliberately destroyed two lives (three, if you count his complicity in Lachna’s fate); and so he is innocent no more. However, Lavond is concerned with the clearing of his name only so far as it frees his family from disgrace and poverty. He has no intention of resuming his old life; instead, he tries, convicts and condemns himself…

In this, The Devil-Doll makes a remarkable connection with another MGM film: The Mysterious Island, which also stars Lionel Barrymore as a decent, honourable man driven by betrayal to violent revenge; and in which he also judges himself guilty. Here, as there, the fact that personal revenge is not considered justifiable, that an eye for an eye is no excuse, comes these days as something of a moral shock.

And there’s another one to come—but we’ll get to that shortly. First, Lavond tries to dissolve his partnership with Malita, making the near-fatal (and, let’s face it, pretty damn stupid) mistake of telling her that he never meant to go on with Marcel’s work, and that “everything in the back room” must be destroyed…and assuming that he’ll then be allowed to just turn his back and walk away from it all.

Instead, Malita re-dips the stiletto and sics Radin on Lavond. She gives herself away, though, glancing at the floor once too often, and Lavond evades his tiny assailant. So then Malita resorts to Plan B, snatching up the usual flask of powerful explosive, without which no laboratory is complete, and threatening to blow the room, herself and Lavond to kingdom come. Lavond tries soft-soaping her out of it – “Now, Malita, you don’t want to do that….” – only it turns out that, well, yeah, actually she does.

Whoa. Atomic Grenade.©

Lavond escapes, of course. He’s already mailed a confession to the police – in the name of Madame Manderlip – and now he has only one thing left to do…or maybe two.

Few dictates of the Catholic Legion of Decency-backed Production Code were as rigidly enforced as the one forbidding suicide in plot-resolution—yet the dialogue of The Devil-Doll makes it perfectly clear that having resolved his family issues, Paul Lavond intends to kill himself. I don’t quite know how they got away with it. Perhaps it was considered a fitting punishment for his crimes (to which we can now add complicity in the deaths of Malita, Lachna and Radin); or perhaps suicide is only suicide if it happens onscreen.

In pursuit of his aim, Lavond reveals himself to Toto, and tells him all about Madame Manderlip, although without revealing what he really means by “my exile”, so that Toto won’t have to keep that secret, at least, from Lorraine.

Toto then arranges for Lavond to meet Lorraine at the top of the Eiffel Tower. It’s “their place”, where Toto proposed; and, with the various journeyings up and down, plays a nicely symbolic role all throughout the film. Lorraine is overwhelmed by the news of her father’s innocence, and distraught at having misjudged him.

Here Lavond approaches her, introducing himself as, “A friend of your father”. He tells Lorraine that he and Lavond escaped together, but that Lavond died during the journey through the swamp—though not before entrusting him with a message to his daughter.

And so Paul Lavond achieves his last ambition in life. He gets to hold his daughter’s hand, to kiss her—and to say to her, “Your father loved you very dearly…”

And damn you—damn you, Lionel Barrymore! Why, oh why, when you could act like this, could underplay as beautifully as you do in this single scene, bringing out the best in Maureen O’Sullivan and Frank Lawton, too— Why did you spend so much screentime carrying on like a twenty-pound Christmas ham!?

I swear, it’s enough to make me want to lob an Atomic Grenade or two myself…

Footnote: Yes, yes… Never mind Paul Lavond’s innocence: it’s the story to the left that interests – and confuses – me. As far as I can make it out, it’s about a specimen of Cacajao melanocephalus, the black-headed uakari. So far so good. Except that the black-headed uakari is found in South America, in Brazil, Venezuela and Columbia, not South Africa. And it wasn’t discovered in 1936. The hell – !?

I don’t think I’ll be turning to the Bulletin Parisien for my zoology news…

Want a second opinion of The Devil-Doll? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

Click here for some Immortal Dialogue!

And once again, if your final benefit is for all humanity, you can kill/maim as many people as you want. At least the scientist doesn’t say, “Science always demands sacrifice.”

LikeLike

It is interesting how completely unhumanitarian movie humanitarians tend to be. 😀

LikeLike

So if I understand the Immortal Dialogue correctly: because everything is made of atoms, and atoms are made of electrons (um…), therefore SCIENCE! However, I don’t quite see where the cotton wool comes into it. I guess I’m no scientist (although I may well be mad).

LikeLike

It’s obvious, cotton wool is made of atoms (and electrons).

The fact that it also prevents the movie from being x-rated is totally beside the point.

LikeLike

Mind you—I only realised after the event how topless Grace Ford looks in that screenshot. But she’s covered in cotton wool, I swear!

LikeLike